Seagulls are interesting birds that have adapted extremely well to human environments and are very successful at breeding and surviving in the presence of humans. This is evidenced by the countless seagulls living in urban environments worldwide.

Don’t forget to check out our General Knowledge Quizzes for a bit of fun before you leave!

If you like birds and want to learn about their migration patterns, check out this article on Why Birds Fly South in the Winter.

Do seagulls sleep?

Yes, seagulls do sleep, although it doesn’t look exactly like when humans sleep. For example, seagulls often open and close their eyes whilst they are sleeping and also they adopt different poses which have been linked to different levels of sleep states.

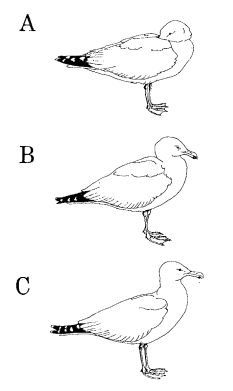

A study in 1981 investigated the sleep behaviour of herring gulls (Larus argentatus) and found that there are three stages of sleep or sleep-like postures displayed. One of which was labelled “sleep” another “rest-sleep” and the last “rest”. Take a look at the image on the right to see how these postures differ.

The postures themselves and the relative rates of eye blinking were found to be indicators of sleeping gulls, with more time spent with their eyes closed in the “sleep” posture.

Sleeping postures of seagulls. A) Sleep. B) Rest-sleep. C) Rest.

Where do Seagulls Sleep?

Seagulls usually sleep in open spaces where they have a good view of their surroundings, often this is in groups with other gulls. Rooftops and other high-up places are where gulls are usually seen sleeping. Interestingly, gulls have been found to sleep in “waves” with groups of gulls going through periods with more and then fewer gulls sleeping in a wave-like pattern.

This behaviour may be an evolutionary strategy to increase the safety of a group, where some gulls are always alert to any potential dangers. It could be the case that more gulls sleeping is an indicator to individuals that it is a safe time to sleep. Two papers published by Guy Beauchamp in 2009 and 2011 studied these sleeping patterns and you can read those articles for a more in-depth picture of this phenomenon.

Seagull FAQ - All of your questions about seagulls answered

Are all seagulls the same?

Although seagulls look very similar and seem to be widely distributed around the Northern Hemisphere, there are in fact several distinct species of gull and none of them are actually called seagulls!

Most gulls are part of the genus Larus and they can be considered medium to large birds with typically black or grey colouration on their wings and webbed feet. They are often seen on the coast floating along in the current.

The most common gulls that you are likely to come across in the UK are the European herring gull, the lesser black-backed gull, the greater black-backed gull and the common gull. There are also a few less common and smaller species which you might have asked yourself in the past, “is that a seagull”. One example is the black-headed gull which appears to be different in the summer and the winter where its head is black in the summer and whiter in the winter.

The Wildlife Trusts has a great page which explains the different species of gulls that can be found around the UK and for more information on the American herring gull, visit this page.

Do seagulls have webbed feet?

Yes! Absolutely they do have webbed feet because they are sea-gulls. They are adapted to living near the sea and coast and are great swimmers. Seagulls can float and paddle efficiently and often sit in large groups in the water, likely paddling to stay near each other.

If you want to learn more about this topic, we suggest you visit learnbirdwatching.com. They wrote a comprehensive article about seagulls and their webbed feet.

What is a baby seagull called?

Baby seagulls are simply known as gull chicks and they broadly resemble their parents with a greyish colouration, although with much fluffier feathers for warmth.

What do baby seagulls eat?

As with the many bird species, their young are fed by regurgitation of food that the parents ate. This means that the diet of seagulls is likely to be the same as their offspring. It is possible though that seagulls who are nesting, adjust their diet to meet the needs of their growing gull chicks.

Unfortunately, it is commonplace to see seagulls eating human-generated waste and in all likelihood, plastics and other harmful objects will be passed on to gull chicks.

Whilst we’re on the subject of seagulls eating, you might have wondered how seagulls can eat almost anything, including large objects such as entire bones.

Seagulls have large mouths and stretchy oesophagi which allows them to quickly swallow unexpectedly big things. They also have a gizzard which is a special structure in the digestive system that aims to break down objects before reaching the stomach, this is what sometimes contains stones that birds have eaten on purpose to help grind down food. If you’re interested, why not read more on the digestive systems of birds.

You may have also seen gulls feeding straight out of rubbish bins and this leads to another question.

Why don’t seagulls get sick from eating rotten food?

It turns out that scavengers such as seagulls have a naturally lower pH of acid in their stomachs, this acts as protection against higher levels of harmful pathogens in their food. This is also why birds such as vultures which are the stereotypical scavengers, have no issues eating rotten meat, also known as carrion.

This lower pH in the stomachs of scavengers is an example of evolutionary changes which follow the adaptations of an organism’s behaviour. As scavengers, scavenge, they evolve to become better equipped to deal with the challenges of scavenging. To read more about the evolutionary link between scavenging and stomach pH, check out this article.

We hope you have learned the answers to your questions: Do seagulls sleep? and Where do seagulls sleep? Check out our other science blogs for more fascinating insights into science concepts. We also wrote a blog about whether or not moths sleep! Also, consider checking out our science quizzes!

About Discover Tutoring.

We are biologists by training and when we write an article we read the scientific literature to find the most accurate answers to your questions. We do not guess, we do not assume, we check the research. If you are interested in our conclusions and want to find out more, check out the references at the bottom of every page we post on nature.

References –

Amlaner, C., McFarland. D.(1981) Sleep in the Herring Gull (Larus argentatus). Animal Behaviour, 29 – 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(81)80118-2.

Beasley, D., Koltz, A., Lambert, J., Fierer, N., Dunn, R. (2015) The Evolution of Stomach Acidity and Its Relevance to the Human Microbiome. PLOS ONE, 10(7): e0134116. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134116

Beauchamp, G. (2009) Sleeping Gulls Monitor the Vigilance Behaviour of their Neighbours. Biology Letters, 59–11

http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2008.0490Beauchamp, G. (2011), Collective Waves of Sleep in Gulls (Larus spp.). Ethology, 117: 326-331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01875.x